Artist Tracey Emin has given an insight into her return to Margate through an interview with

When Covid-19 brought the art world to a standstill in the spring, shutting down galleries and museums worldwide, Tracey Emin, one of Britain’s most famous living artists, was already upending her life.

As lockdowns spread across Europe, Emin was preparing to move from her home in East London, where she’s lived for the past 22 years, into a big new place in the centre of the city, a neoclassical spread with plenty of room to make art. And she was building a second home outside the city, a residential studio complex in a vast industrial space in her hometown, Margate.

I met Emin at her new place in Margate last year, before the pandemic hit, when construction was still in full swing. “I might be working on 30 big canvases all at once here, really large ones,” she says, imagining the possibilities for her new painting studio as we toured the dust-filled construction site. “I’d be really free, almost like a conductor, to just go crazy like a banshee or something.”

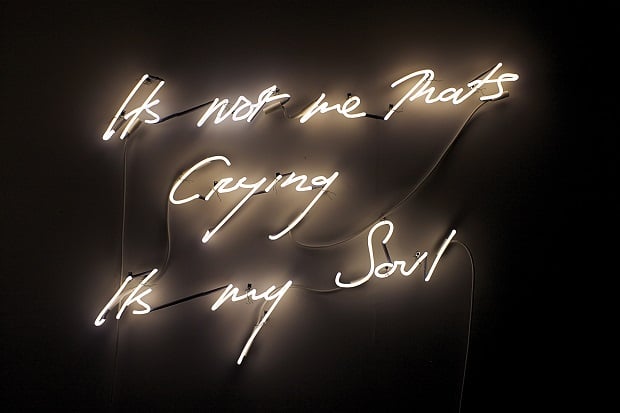

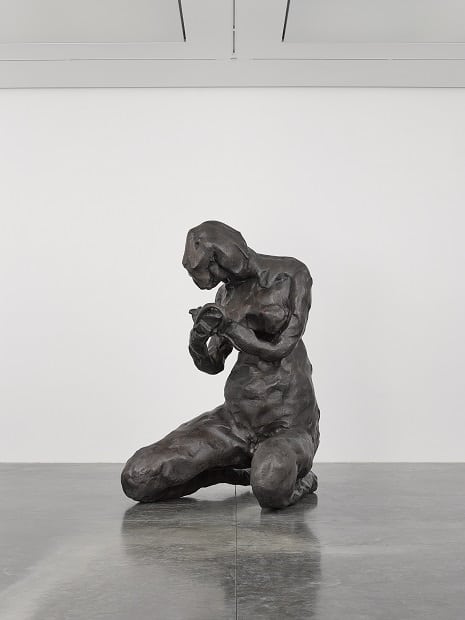

Emin is best known for her intense autobiographical work across many mediums, baring her soul in fabric, film, photography, wood, found objects and her own handwriting in bright neon. She’s shifted her focus in recent years to more classical painting on canvas and hands-on clay sculpture. “She’s making less of a variety of kind of artwork, but she’s becoming more and more who she is—which is a painter and sculptor where everything is made by her, where there’s no foil between her and the work,” says art dealer Lorcan O’Neill, a friend since the 1990s who represents Emin in Rome through his gallery there.

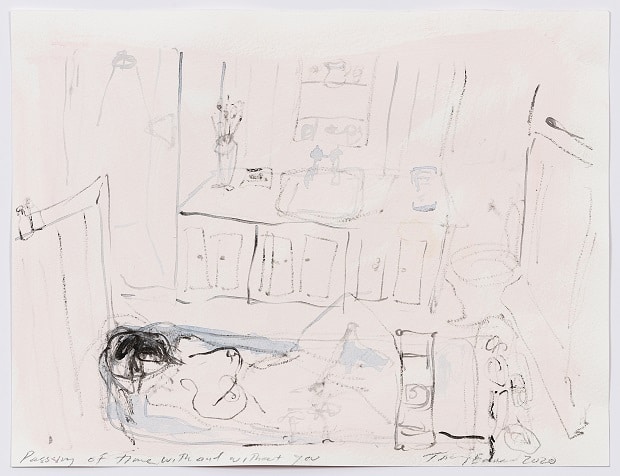

Emin’s acrylic paintings, in feral drips and streaks, often layer one image onto another. Spectral figures hide under whitewashes or violent bursts of dark colour, often with poetic, sometimes raging language scrawled on top. “I’ll start off with one idea and then as I go along, I’ll go, ‘Oh, my God,’ and something else comes out,” she says of her process.

Her more recent body of work is a major departure for this former “bad girl” of the British art world, who burst onto the scene with the Young British Artists of the ’90s with confrontational pieces like her appliquéd tent listing Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, and her Turner Prize–nominated My Bed, reproducing her unmade bed after a four-day bender, with crumpled sheets, spent condoms, empty vodka bottles and a pregnancy test.

Emin, now 57, started considering her legacy long before the coronavirus brought our collective mortality in focus. In January 2017, she bought her 30,000-square-foot stretch of the derelict Thanet Press building in Margate, ravaged by looters, pigeons and long, salty winters. “It looked like the set of some apocalyptic film when I found it,” she says. The site, she hoped, would become her final residence and, eventually, the posthumous home of her personal museum and archive.

This summer, that long-range thinking began to look tragically prescient. In June, a few months into her lockdown in London, Emin learned that advanced bladder cancer – “really bad cancer,” she calls it—had begun to spread to her internal organs. “I didn’t really want to tell anybody at the beginning because I didn’t know if I was going to die or not,” she says, reached by phone in late September.

Emin had an operation in July that left her cancer-free and, for weeks afterward, too rundown to make art. She was still recovering in September when she returned to Margate, to look in on the work there, for the first time in months.

Her return to Margate marks the culmination of a period of deep introspection, a reordering of priorities that began shortly before her mom’s death from cancer in fall 2016. That summer she announced a radical retreat from public life.

Emin on her painful upbringing at Margate

After their dad’s business went belly-up in 1972, their mother, Pam Cashin, turned to squatting in the hotel’s staff cottage, with the kids left to fend for themselves while she worked every job she could find. “Being in the hotel, being left alone, made us very vulnerable as children,” says Emin. “And this was quite difficult for my mom when she got older, and she felt terrible about this. And my dad was mortified…. There were all these people that came into our lives constantly—through a door, out the back door, this lodger, that person…. It wasn’t my dad’s fault. It wasn’t my mom’s fault either. It was like this sort of f—ed up, dysfunctional train of events.”

Carl Freedman, an art dealer and an ex-boyfriend from the ’90s with whom she’s still close on taking Emin to Margate in 2016: “She came down, looked over the whole place,” recalls Freedman. “‘This is fantastic,’ she said, ‘but the idea of going back to Margate, I just can’t face it.’ ”

Emin on deciding to return to her hometown:

One day that fall, learning that her mother was on her deathbed, Emin visited her in Margate. Emin’s feelings about her hometown started to change. “I was thinking, When my mom dies there’s no reason for me to come here, no reason for me to be here anymore,” she says. “I didn’t feel happy with that idea. This place is in my psyche. It’s part of me.”

“I need the true memory,” she says. “I don’t want to romanticize. I want to try and remember how it really felt, and then I want to put that in my work. I find if I’m painting stuff that really means something to me, the closer I am to it the more inspired I’m going to be.”

Emin on her show at White Cube early last year:

A Fortnight of Tears, her first solo show in London in five years, which drew blockbuster attendance, debuted at White Cube south of the Thames, displaying Emin’s grief over her mother’s death channeled into paintings and sculptures. “When my mom died, I cried so much,” she says. “But after a couple of weeks there wasn’t any more to come out. You have to get up and get on.”

Emin on working nonstop after the White Cube show:

“Everyone said to me, ‘Why are you working so hard?’ ” she says. “I was going, ‘Because you never know when you won’t be able to work hard.’”

Jay Jopling, London gallerist, founder of White Cube: “So much of her artistic output draws from her childhood traumas. “Margate was always in her, always in the work even when she kind of left Margate far behind.”

Emin on Gabriel Chipperfield (son of architect David Chipperfield) her friend and former design consultant on the Margate project:

Chipperfield eventually stepped away from the project to preserve their friendship, says Emin. Now she oversees every design detail herself in consultation with an architectural engineer. “You don’t want to wreck your friendship because you disagree on whether something should be clad or the steel should go here or there or whether the concrete should be raised or lowered,” she says.

Emin on the Covid shut down:

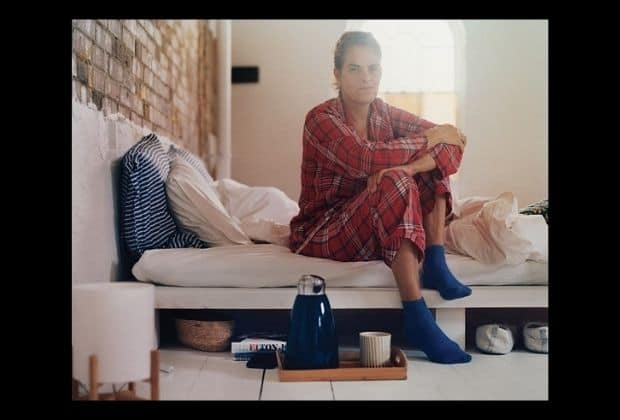

“I’m used to isolation—it’s where I thrive,” she says of the time alone. “I had a fridge full of food, it was cosy, the weather was amazing. And I was painting about four days a week. I’d go to the studio on a Monday and stay there through Thursday, sleep on the sofa. I was working all night sometimes and sleeping on the sofa all day and not getting dressed and just swimming. I just loved this experience of being in this bubble, me on my own.”

Emin on her upcoming at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, pairing Emin’s work with an idol’s—Norwegian painter Edvard Munch:

“Since I was 18 he’s been my favourite artist,” she says. The presentation, originally scheduled to run through February, will move to Oslo next year, for the opening of the new Edvard Munch museum. Emin’s 23-foot bronze sculpture, The Mother, will be a permanent fixture on Oslo’s Museum Island, opposite the Munch museum.

Emin on what’s next:

Work continues, meanwhile, on Emin’s new home-studios in central London and Margate. She hopes to be living between them by the start of the year. “I’ll spend one last Christmas in [East London] and then change my life for good in 2021,” she says. “Margate is perfect for a museum. I don’t have to worry about my legacy: I’ve created a place for my work that will work perfectly.”

All photos Thurstan Redding for WSJ. Magazine