Many adults are still haunted by memories of clinical settings that they encountered as a child – be it a dentist’s chair or doctor’s waiting room.

A mere hint of the smell of antiseptic in the air, or the sight of syringe can make the toughest and strongest wince.

For those who work in the fracture clinic of Margate’s Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother Hospital, it comes as no surprise that children can easily be upset by medical settings – and this can make the treatment even harder.

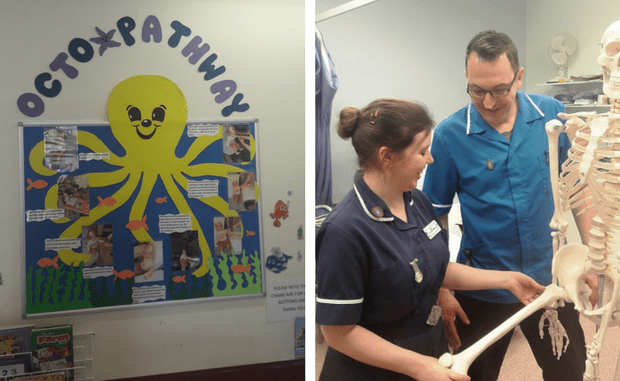

But there is something special about one area of the fracture clinic, which is clearly designed for children. It is home to an image of a giant, mustard-coloured octopus looking down on you, complete with reassuring smile. Clinical it isn’t, captivating it most certainly is.

Above the sea creature it says “Octo Pathway”, and each tentacle is accompanied by words describing the medical journey a child takes when they have the misfortune to break a bone. The text also has pictures of a doll called ‘Molly’ who has to attend the fracture clinic. According to the text, Molly enjoys her healing experience.

Orthopaedic practitioner Robbert Peters says: “That’s the beauty of it – the Octo Pathway gives adults an insight into the process of mending a fracture. It takes away the fear factor, and we’re doing it in a very visual way.”

That, essentially, is what the Octo Pathway is all about. It’s a pictorial aid that children and adults can refer to while they’re in the clinic. And below the giant octopus is a diminutive red table, surrounded by equally diminutive colourful chairs and a scattering of toys. In case any adult is tempted to take advantage of the chairs, a friendly note advises that the furniture is for “little bottoms only”.

There is no magic medicine or radical approach in the Octo Pathway – it simply draws upon the instinctive curiosity of children, their imagination and their need to feel at ease.

Robbert is a huge fan of the benevolent octopus and admits that he simply “loves” working in the clinic and working with children and their parents.

The walls of part of the fracture clinic are testament to that work by Robbert and the team. They are home to cards and envelopes, some written by adults – but many penned by children – that express gratitude for wounds mended and care given.

Robbert points at one that stands out:“A little girl fell off a bike and had a really nasty leg and ankle fracture but we got to know her and her family, and she became interested in the medical process of mending a fracture. The trauma of what she experienced began to go and she really appreciated the care she was given – and now she wants to be a doctor!”

Each month the fracture clinic can receive up to 70 children, most of whom live in Thanet, Deal or Canterbury. The usual causes of broken bones include accidents arising from in a gymnastic class or using roller skates, skateboards, scooters and trampolines.

First introduced in 2015, the Octo Pathway is the creation of a former colleague, Steve Hackett-Cam, and Louise Walker. Louise still works in the fracture clinic as an orthopaedic practitioner alongside Robbert, and is proud that her mum, Audrey Walker “brought the octopus to life” with clever artwork.

Louise says: “Molly’s journey next to the octopus is a guide for parents. They can look at it and see what’s happening to the children. If a parent is anxious, the child will pick this up. Some parents consult ‘Dr Google’ and this isn’t very helpful – they can sometimes get confused and concerned for no reason at all.”

The Octo Pathway, with its illustrative octopus and reassuring text, has the capacity to calm parental nerves.

In reference to Molly, the text refers to children who are hurt as ‘poorly’. It also advises that Molly needs a plaster, but she isn’t sad because “she can choose a pretty colour”.

We’re told that Molly’s bones healed because the “hard plaster” kept them safe until the friendly doctor is pleased with the progress. When Molly’s plaster can be removed, a special ‘tickly machine’ is used to do the job.

Louise said: “It’s made a huge, huge difference. We treat our young patients like patients, and we never forget that pain is a very personal thing.

“We treat the child, but we never forget we have to tend to the parent too.”

Feature by Steve James