By Dan Thompson

Turner Contemporary’s galleries reopen on Saturday (22nd October) with two new exhibitions.

And while one is amongst the most spectacular and colourful the gallery has ever staged, the other might be the dullest yet.

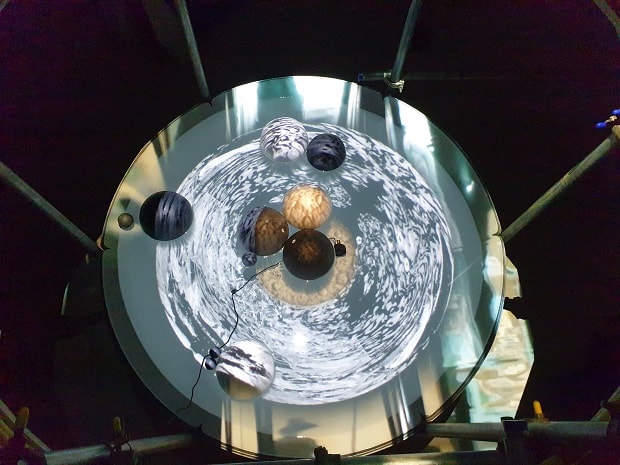

The exhibition by Lindsey Seers and Keith Sargent, is one of the most interesting things Turner Contemporary has staged in recent years. In one room, a huge platform built of scaffolding lifts visitors above a circular pool filled with balls rotating like planets in a solar system.

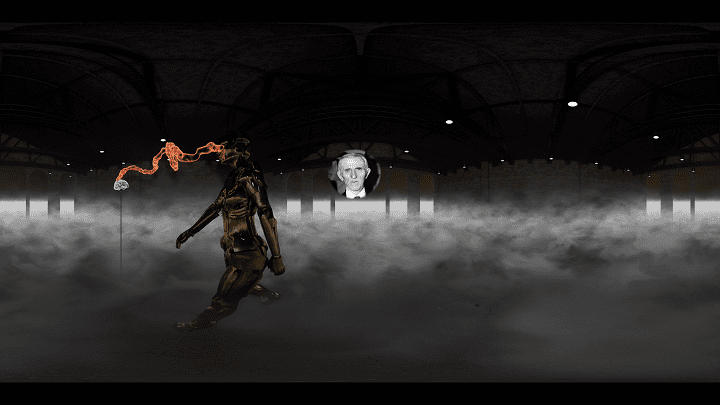

Elsewhere, ducting has erupted from the floor and a weird mechanical monster twists and turns as it stalks visitors. There are projectors everywhere. Strange noises bubble under and official voices make announcements. This is a science fiction world, like something from Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass or Sylvester McCoy-era Doctor Who.

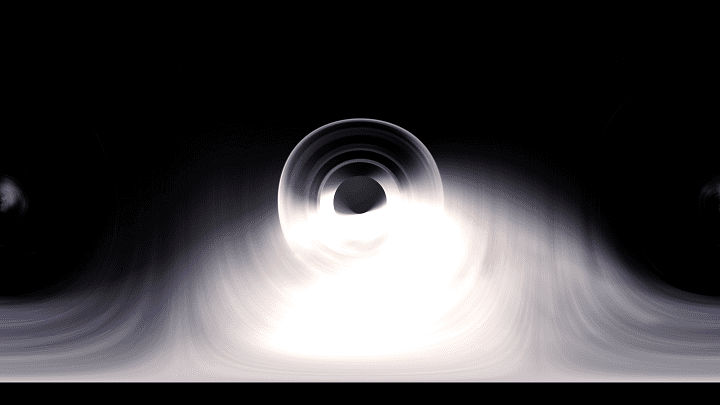

In another room, six people at a time sit in strange geometric pods (their shape is also seen in the main room) and immerse themselves in a Virtual Reality world.

The whole work is called Cold Light, its title inspired by historic references to the first electric light bulbs. No longer reliant on fire for illumination, the new electric lights were referred to as ‘Cold Light.’

It’s a captivating experience – it feels like you’ve wandered into a space you’re not supposed to be in. None of it makes sense, but all together it has its own weird, wonderful logic.

Of course it will cause the ‘I don’t understand modern art’ crowd to stamp their feet in confusion. But immerse yourself in it, let it wash over you, don’t worry too much about trying to understand it, and it’s incredibly entertaining.

The other exhibition is dull and that dullness is no reflection on the artist: he died, aged 29, in 1982. It’s hard to imagine that Stephen Cripps would ever have wanted this exhibition to be held.

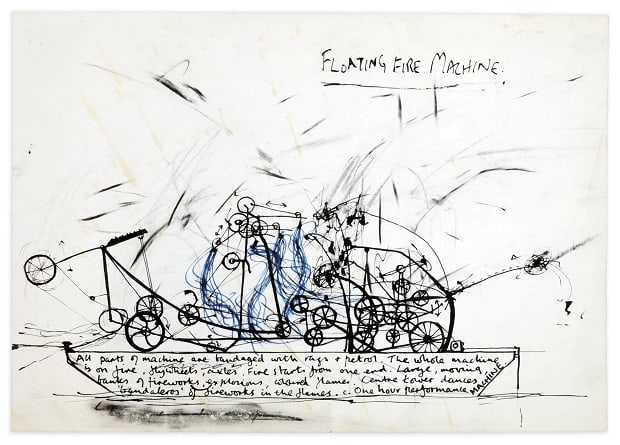

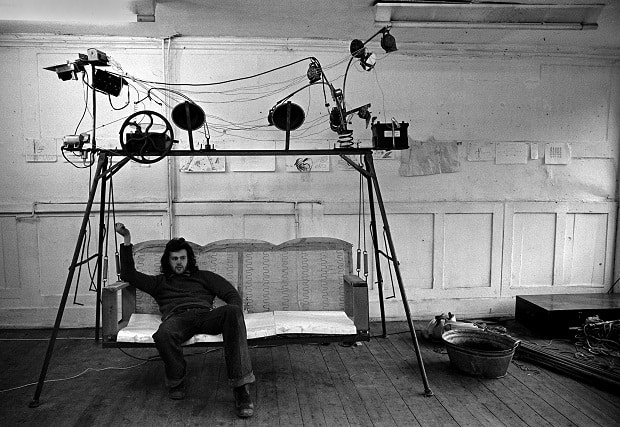

He was part of a wave of artists in the 1970s who took advantage of the death of London’s industries and opened studios, workshops, and galleries in old warehouses and factories across the city. From his huge studio at Butler’s Wharf – today, a collection of high-end shops and white wall galleries just along from Tate Modern – he made brilliant work, mad machines, scrap metal sculptures that moved and breathed fire.

He designed dramatic modern stage shows for Stephen Berkoff (including Kafka’s Metamorphosis at the National Theatre) and he created post-apocalyptic performances with artists working with sound and with musicians like Michael Nyman and David Toop.

It was an incredibly exciting time for the arts – rules were being broken, new ways of working invented, and people collaborating across different genres.

But sadly, this exhibition fails to capture that excitement, and presents nothing but his paper archive, and a few short films. You could easily spend an hour looking at the hundreds of drawings, notes, letters, and photographs and still have no idea who Cripps was or what he did. His machines, his sculptures, and the physical objects that fill every corner of his studio in photographs are not on show.

Only one seems to still exist, a thing the size of – and possibly made from – an old push-pull lawnmower. There is no suggestion of what it did. It’s a dead thing.

For Cripps, art was a living thing, that existed either in performance or in the interaction with an audience. It was alchemical, using the elements – air, water, earth, and fire (he even became a fire officer, to learn more about combustion!). Cripps’ wouldn’t have wanted his work reduced to hundreds of pieces of lifeless paper in display cases under Perspex.

It’s hard not to think that Stephen Cripps work, experienced live, probably had a similar impact at the time to that of the Seers and Sargent’s exhibition now.

Lets hope that, 40 years from now, we’re not just looking at Seers and Sargent’s working drawings, technical plans, and out-of-focus photos of the work.

To make sure you’ve experienced the real thing, head to Turner Contemporary before 8th January, when the two exhibitions close.