“I’m writing a book with a poet!” I announced proudly to my friend Andrew.

“Really? Do you dip his floppy locks into an ink well? Doesn’t he squeak a bit when you push him over the page? I’d try a biro if I were you. Poets are notoriously fickle.”

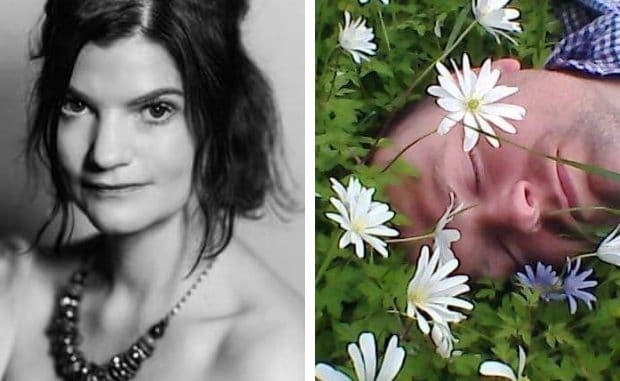

I slap him while bellowing that actually, this one’s far from fickle. Matt Chamberlain has brought out seven books already and he’s working fiendishly hard to bring out an eighth with me, against all possible odds. I don’t write books. I don’t write poetry. I like poetry enormously, but I’m also suspicious of it. Anything so richly seductive, indulgent, transformative, can’t be entirely wholesome, surely?

So when, having encountered and admired each other’s work online, we found ourselves writing a book together, that was the first of many seemingly insurmountable problems. What possible reason could there be for a book partly written in sublime poetry, part in mundane prose? We spent months coming up with such terrible ideas that I still blush to think of them. There needed to be a story, an over-arching narrative, beyond wanting to write a book with a pal because hey, writing a book on your own is like, dead hard and really scary. We needed a tale that could be told in poetry and prose, where our conflicting styles could be a strength, rather than simply baffling. When we got an idea, it was so obviously the only possible and simplest of ideas, as all great ideas are, that we wasted a few more months bashing our idiot heads against our respective brick walls.

No spoilers. But I will tell you that in our book a woman encounters and admires the work of a poet online, and they strike up a correspondence. The woman in question is quite like me, but me at my worst, vain, self-obsessed, self-indulgent, hysterical. I’ve very much enjoyed giving free rein to my worst qualities all these months, although I suspect I’ve been hell to live with.

When you’re in the throes of an intriguing creative project, it consumes you utterly. You start to forget which is truth, which fiction. They blur alarmingly in the brain. And not yet having got to the end of our fictional story, I’m struggling to present to you our actual story. They do, after all, contain striking similarities. Woman meets charismatic wizard and has her life transformed. So far, so simple. It’s Rumpelstiltskin, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella. But how did the woman feel? Well, she isn’t sure yet. And what was her story before the wizard arrived? Well, there it depends who you ask.

We all tell ourselves stories to make sense of our lives. We process our relationships in metaphor: they’re too complex to fathom otherwise. For instance: I’m rubbish at maths because my mum was rubbish at maths; I deserve the cake because I’ve had a hard day; she’s ignoring me because she’s jealous of my success; he’s quiet because he’s shy, not because he hates me; she tries to do me down because she’s insecure since her husband left. Brown terrorists are religious fanatics; white ones are mentally ill lone wolves who were rejected by a girlfriend. They’re all just stories, one possibility among millions, palatable, attractive explanations.

Writing a story about how a dumb schmuck like me came to be writing a story with such a prestigious talent makes me realise how little of either story I understand. I’m too deliriously thrilled at the unexpected plot twist to fully comprehend it. But I do hope that if I own this story then I get to write the ending. It’s to this hope I cling.

Our book is called Letters. I’m incredibly proud of it, and I’ll miss it when it’s left my laptop and ventured into the world. Do look out for it.