Crime writer and Cardiff University professor Jan Bondeson is the author of a book of 56 Victorian cases of murder that were covered in the sensational weekly penny journal the Illustrated Police News between 1867 and 1900,

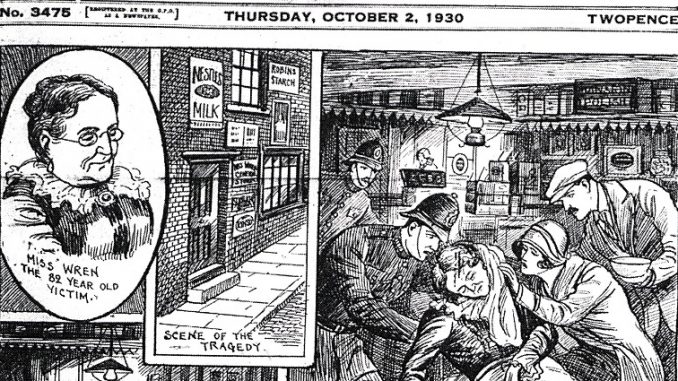

The Illustrated Police News was an early form of tabloid paper, using graphic sketches to illustrate its stories.

It and others like it were referred to as Penny Dreadfuls, as they cost just one penny for a weekly digest of eight, murder packed pages.

Dr Bondeson has already shared the ‘Ramsgate Mystery’ of 1893 and the story of the murderous Ramsgate ganger Samuel Henson with The Isle of Thanet News readers from the book, Victorian Murders.

Her third, and final, offering is the mysterious murder of Ramsgate sweet shop owner Margery Wren.

Victorian Murders was published by Amberley Publishing on December 15 is available here: https://www.amberley-books.com/victorian-murders.html

The unsolved murder of Margery Wren

Margery Wren was born at No. 3 Charlotte Street, Broadstairs, in 1850, daughter of the house-painter William Wren and his wife Elizabeth. She had at least one sibling, the five years older sister Mary Jane. Margery Wren went to London to become a servant, and the 1871 Census lists her as being in service in Islington, whereas the 1881 Census finds her living with her parents at No. 42 Spencer Street, Clerkenwell, and working as a maidservant.

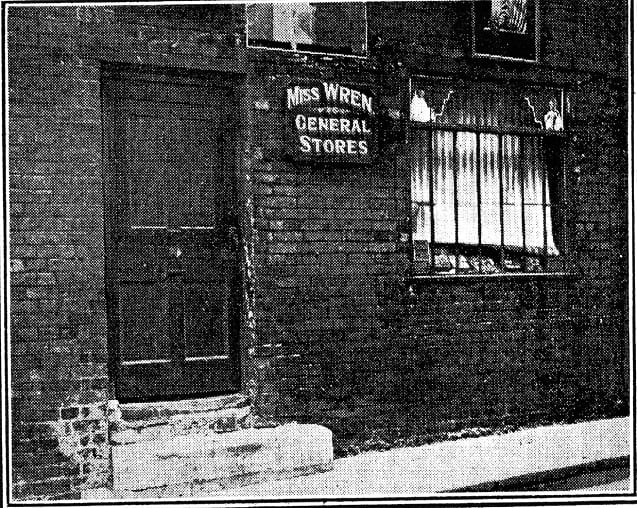

In 1891, she was still servant to a London merchant, but a few years later, an old lady named Mrs Wroughton died in Ramsgate. She was related to the Wrens, and Mary Jane and Margery inherited a sum of money and an old confectioner’s shop at No. 2 Church Road, Ramsgate.

Mary Jane and Margery were quite happy to escape the London drudgery, and they set themselves up in their new shop. The Church Road house was far from a luxury dwelling, containing the shop and a small parlour on the ground floor, and two bedrooms on the first floor, but the two Wren sisters were used to cramped and insalubrious living conditions. There was no bathroom, and the toilet was out in the yard. The 1901 Census lists Mary J. Wren as a Confectioner, and head of the household, and the younger sister Margery as cook.

In 1911, the Wren sisters were 65 and 60 years old, respectively, but they still tended their “Cottage sweets and General shop” at No. 2 Church Road. Mary Jane Wren died a spinster on January 31 1927, leaving the shop and £921 12s. 7d. to her sister. Margery Wren did not use this money to lead a life of luxury, or make any effort to improve her living conditions; she stayed in the old shop, which had been old-fashioned already in the 1890s, and which had become obsolete by the late 1920s. She dressed in archaic attire, with a woollen cap protecting her balding head, and wearing very long skirts.

On Saturday September 20 1930, the 80-year-old Margery Wren was tending her little shop at No. 2 Church Road, just as usual. There were a few customers from the nearby St George’s School, the children remaining loyal to their local ‘tuck shop’, in spite of its elderly owner and insalubrious interior. As the children returned after their luncheon break, masticating the rock-hard sweets from Miss Wren’s glass jars, calm and quiet returned to the little shop and its octogenarian owner.

Half an hour later, the coal-dealer Reuben Beer delivered half a hundredweight of coal at No. 2 Church Road, and Miss Wren paid him a shilling and twopence for it. At 5.15 pm, Margery Wren was seen by some children, sweeping leaves away from the front of the shop. At about the same time, a well-dressed woman with a red hat came calling at the shop, leaving a perambulator outside.

At shortly after 6 pm, 11-year-old Ellen Marvell came up to the shop at No. 2 Church Road, on an errand from her mother, to purchase some blancmange powder. Since Miss Wren was known to keep her shop open at late hours, Ellen was surprised to find the door to the little shop locked, and she knocked it hard to alert the elderly shopkeeper. It took quite a while for Miss Wren to answer the door, and when she finally opened, Ellen could see that she was looking quite bedraggled, and that she was bleeding badly from the head.

Although frightened by the appearance of the old woman when she came staggering up to open the door, Ellen’s main thought was the blancmange powder, and she finally managed to get through to the dazed shopkeeper what she wanted. Miss Wren had quite a supply of blancmange powder on the premises, and she had Ellen select what flavour she wanted. Ellen Marvell ran home and told her father what had just happened. When he went to the shop, he found Margery Wren collapsed on the floor, and he sent his two daughters for a doctor and a police constable.

When Margery Wren regained consciousness, she explained to Mr Marvell that she had fallen down hard and hurt her head. When Dr Richard Archibald, a veteran Ramsgate practitioner who had been looking after the medical needs of the Wren sisters for many years, came to the shop, he could see that the old lady’s extensive injuries were clearly not the result of a fall, but to multiple lacerations of the head by some blunt instrument. A pair of blood-stained fire tongs, which were laying on the floor, were a prime candidate for being the blunt instrument in question. Miss Wren told Dr Archibald that she had been assaulted inside the shop: “He caught me by the throat, and then he set about me with the tongs.” When the doctor asked her to name her assailant, she just said “You will never get him, doctor. He has escaped.” Dr Archibald found it strange that for some reason or other, Miss Wren did not want the name of her attacker to become known.

Margery Wren was taken to the Ramsgate Hospital, where she lingered for five days. She spoke confusedly about what had happened to her, telling Dr Archibald, a policewoman and various other people that “They were two of them set about me. If I had not had my cap on they would have smashed in my brain-box.” She then said that there had been three, or even four, assailants. She accused an elderly man named Albert Williams of having been the man who attacked her, but then pointed the finger at “Hamlyn of No. 19”.

Several times, she said “Hope did it!”, once adding “Hope of Dene Road!” Mr S.F. Butler, the Chief Constable of Ramsgate, communicated with Scotland Yard, and Chief Inspector Walter Hambrook was dispatched to Ramsgate to take charge of the murder investigation. When he arrived on September 24, Miss Wren had become comatose, so it was impossible for him to question her in person. Hambrook was quite baffled by the contradictory statements from the dying woman, accusing a number of respectable, elderly people of having attacked her. When the magistrate had come to take her dying depositions, she had merely said “I do not wish him to suffer. He must bear his sins. I do not wish to make a statement.”

The local vicar had been equally unsuccessful in getting Miss Wren to denounce the identity of her attacker; after he had left frustrated, Miss Wren said, with a note of satisfaction, ‘I did not tell him anything, see’. The badly injured old woman died on Thursday September 25, and the case was now one of murder.

The scene

Walter Hambrook went to see the murder shop, which was quite a dismal sight, the premises being in a very dirty and verminous condition. There was not much stock in the gloomy old shop, and he got the impression that very little business was done in there. The shelves contained a variety of archaic merchandise: a variety of fly-papers, Sunlight soap, Zebo for cleaning the grate, and Bird’s custard powder, along with a selection of rather unappetizing sweets kept in old-fashioned glass jars.

Miss Wren had told some people that she was the owner of valuable house property in London, but she had told others that she was very poor, and had even had her meals at a soup kitchen for the destitute. Hambrook thought it likely that Margery Wren knew the man who had assaulted her, but that for some strange reason, she had wanted to keep his identity a secret.

The beneficiaries in her will were two elderly cousins: Mrs Hannah Cook, 72, and Mrs Ann Wilson, 84 and an invalid. Neither of these two were physically capable of committing a violent assault, but the police were interested in Hannah Cook’s son, Police Constable Arthur Cook, but he had an unblemished record, and his clothes were free from blood stains.

Accused

There was brief optimism when a prisoner named John Lambert confessed to committing the murder, but when questioned by Walter Hambrook, he told many untruths, and was incapable of describing the topography of Ramsgate. On her deathbed, Miss Wren had mentioned the name of Albert Williams, a 69-year-old man from Dover, who had visited her at 1pm the day of the murder, to complain that his nephew was leaving him and his wife, to find lodgings elsewhere, but nothing transpired to link him with the murder.

Miss Wren had also mentioned ‘Hamlyn of No. 19’, and there was a young butcher’s assistant named Arthur Hamlyn at No. 19 Church Road, who had once accidentally nearly run Miss Wren down on his motor bicycle, but he had an alibi for the time of the murder.

The coroner’s inquest on Margery Wren was opened by Dr F.W. Hardman on Friday September 26, at the police station parade room. It would go on for many weeks to come, with scores of witnesses examined, although at the advice of Chief Inspector Hambrook, none of the people denounced by Miss Wren on her death-bed were named in court. Hannah Cook the cousin gave evidence about the hermitical habits of the deceased, and her neglect of the house and shop, which were never cleaned.

Confused

She was supposed to have kept some of her money and valuables in a small black bag, but although the bedroom at No. 2 Church Road was found to contain a bag with £8 10s. in notes, and another full of buttons, none of these bags was black. Dr Gerard Roche Lynch and Sir Bernard Spilsbury recounted the medical evidence: Miss Wren had been seized hard by the throat in an attempt to strangle her, and then beaten down with repeated blows to the head with the iron tongs.

A policewoman, who had been present in Miss Wren’s room at the hospital, gave a lengthy account of the dying woman’s confused mutterings on her death-bed. In spite of a police appeal, the woman in the red hat, who had visited Margery Wren’s shop shortly before the murder, was never identified. The coroner’s inquest went on until October 24, returning a verdict of murder against some person or persons unknown.

Since Miss Wren had more than once said ‘Hope did it! Hope was the one who did it!’ every person in Ramsgate by that name was investigated. There was a man named Hope living in Dene Road, but he was 84 years old and his two sons had both been in Tunbridge Wells at the time of the murder.

Charles Hope

The police were interested to find another suspect living at No. 88 Church Road, namely the 20-year-old thief Charles Ernest Hope. He had once been a private soldier in the Royal Corps of Signallers, but had been discharged for larceny. After spending some time in Borstal, he was arrested in London on August 27 1930, for stealing jewellery worth £10 from a bag in the luggage compartment of a train. The police found out that Charles Ernest Hope had spent September 18 and 19 at the Salvation Army Hostel in Euston Road, but on the following day, he had travelled from Victoria to Ramsgate by train, arriving at 4pm and reaching the house of his parents in Church Road at 4.20pm.

There were bloodstains on his jacket, trousers and kit bag, which he explained by claiming to have injured himself when cutting the bag open during the robbery back in August, but the police inspector who had arrested him denied that he had any fresh cuts on his hands at the time. Hope also lied about his movements the day of the murder, claiming to have left the train at Dumpton Park rather than at Ramsgate. He was clearly a petty crook, and perfectly capable of robbing Miss Wren, who was reputed locally to be hoarding money and valuables in her little shop.

Newspaper tales

As time went by, and the police detectives were baffled, there was several unverified newspaper anecdotes about the two Wren sisters. According to one version, they had been servants in a wealthy London household when the daughter of the householder, a person of quality, had given birth to an illegitimate child. The two Wren sisters had taken care of the little girl, and brought her up, for a liberal allowance. This story disregards that no person had seen any little girl at No. 2 Church Road.

Another newspaper story said that the two Wren sisters had once been servants to a wealthy Admiral who lived in Portman Square, and that he had rewarded them well for their work, and given them his framed photograph, which was hanging in the parlour of the murder house. No Census record supports this version, however: although the two sisters were in service in London for some considerable period of time, their masters were gentlemen without any nautical ambitions.

A more adventurous version said that the two sisters were related to none less than Sir Christopher Wren, and that the portrait of another distinguished member of the family, Admiral Wren, was hanging in the parlour. Unfortunately for this version, there does not appear ever to have been a British admiral by that name.

Finally, the most sensational story told that Margery Wren had once herself given birth to an illegitimate son, and that it was this individual who had returned to Ramsgate to murder her. Once more, there was no medical evidence that the Ramsgate murder victim had ever given birth to a son, and no person had seen a little boy at No. 2 Church Road; the police file on the murder makes no mention of either of these newspaper concoctions.

Investigation

Although no person was ever charged with the murder of Margery Wren, the police file makes it clear that there was a main suspect, namely Charles Ernest Hope, for some obscure reason called by the police ‘Ernest Charles Hope’. He lied to the police about his activities the day of the murder, and his clothes were stained with blood. As a petty crook, it would not have been out of character for him to try to rob the shop at No. 2 Church Road, to steal the money he had presumed Miss Wren had been hoarding; nor would it have been beyond him to try and strangle her, and then beat her down, when he was caught searching the house. According to his birth certificate, Charles Ernest Hope was born on October 1 1910, at No. 88 Church Road, Ramsgate, son of the journeyman house-painter Charles Hope and his wife Louisa. He was never named as a suspect in the Wren murder investigation, and his sole newsworthy exploit would appear to have been the following one, from the Hartlepool Mail, August 16 1930:

‘Exceedingly mean’

Ernest Charles Hope, a private in the Royal Corps of Signals, was bound over at Scarborough for what the chairman of the magistrates described as an exceedingly mean trick. He collected for Scarborough Hospital on Rose Day, and, it was alleged, stole 3s. 11d.

This may well have been the caper that earned Hope the sack from the military. For the remainder of his life, he would appear to have stayed out of serious trouble, and the online newspaper archives mention nothing about his activities. Charles Ernest Hope married his wife Mary Rosamund, turned his back on his former life of petty crime, became a foreman carpenter, and moved to Langley near Slough. He died from a burst duodenal ulcer in January 1983, surviving Miss Wren by 53 years.

Chief Inspector Hambrook had occasion to question the parents of Charles Ernest Hope, and they told him that Margery Wren knew both them and their son. Thus, if Hope had been the man who assaulted Miss Wren, then she would probably have recognized him, although the shop was very dark. It is natural for a person who has just been subjected to a murderous assault to make sure that the culprit is identified, but although Miss Wren more than once spoke of ‘Hope’ as the guilty man, she never mentioned his first name or called him ‘young Hope’; instead, she spoke of ‘Hope in Dene Road’ although this referred to an octogenarian acquaintance of hers.

If the young thug Charles Ernest Hope had been the guilty man, there is no particular reason for Miss Wren to protect him from the police: he was clearly an objectionable person, for whom she could feel little sympathy.

Perhaps the true solution to the murder of Margery Wren lies in the speculation about hidden fortunes, mysterious adoptions and illegitimate children, but these variants of the story are never discussed in the matter-of-fact police file.

The murder house at No. 2 Church Road still stands, although it is no longer a shop but a private residence: this little house is a monument to a most intriguing Ramsgate murder that never will be satisfactorily solved.