By Dan Thompson

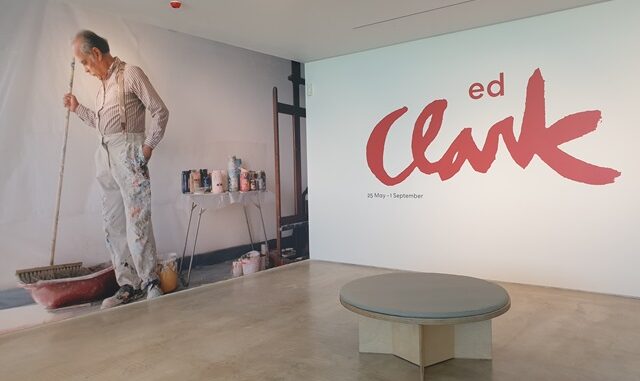

Ed Clark is an unlikely choice for this summer’s show at Turner Contemporary, a slot often given over to a popular artist in an attempt to pull the crowds.

Clark’s not a big, popular name – he was, for most of his seven decade career, an artists’ artist, recognised more by his peers than by the public. And he’s an abstract expressionist, a movement that’s never caught on in the UK in the way it did in the USA. The only abstract expressionists UK audiences are likely to know are Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

This is Clark’s first major show in the UK, and two thirds of the works here are previously unseen in the country. This meets the aim of Turner Contemporary’s director Clarrie Wallis, of finding overlooked artists and giving them major shows. But it makes it a hard sell.

Clark started out as a realist – painting recognisable things, spending two years on a single portrait that is shown here – but studying in Paris after the Second World War (he had served in an all-black unit in the US Army Air Force, and former GIs were given support to study), he became an abstract painter.

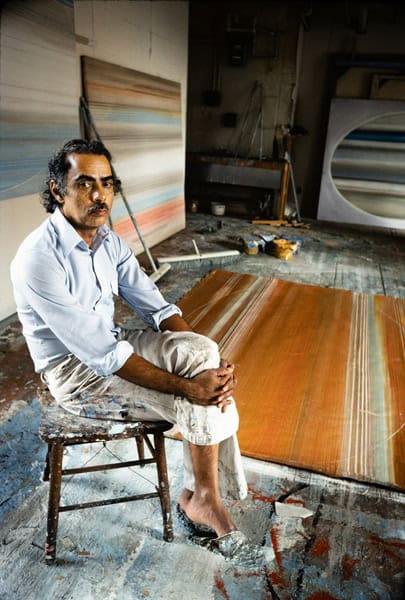

He said that all paintings should be about painting – “the truth is in the physical brushstroke and the subject of the painting is the paint itself.” He became interested in finding ways to make big, dramatic marks on his canvases and used brooms rather than paintbrushes to create his distinctive ‘big sweep’.

Some of the works here are massive in scale – the biggest is nearly six metres wide – and are impressive physical objects. He clearly needed big brushes to meet the scale of his ambition.

The show spans the whole of the second half of the 20th century. The earliest work was finished in 1949, and the most recent painting is from 2005. That means that there are a range of styles and techniques in the exhibition. What’s really striking, though, is that Clark ends up where he began – the 2005 painting is closer to the works from 1963 and 1964 than it is to most of the works painted in between.

Gallery One shows work painted between 1957 and 1967, and these are tough, gritty works where thick layers of paint make bold, rhythmic shapes. This is real abstract expressionism, and in Untitled (1957) Clark can’t even keep the painting within the rectangle of the canvas, bursting out at the edges.

Blacklash (1964) was painted in response to the murder of 15-year-old James Powell by an off-duty police officer, and the ensuing protests which were brutally supressed. It suggests that Clark was already using abstraction to paint about real things, despite his words about paint being the purpose.

Room 2 takes this further. This room features paintings from the 1970s. While Clark said he wasn’t a landscape painter, every work in this room has a sense of place about it.

Clark travelled widely – I spotted mentions of Brazil, China, Crete, Egypt, Mexico, and Nigeria, alongside his time in France, his original home in New Orleans, and years in New York. And the paintings reflect these different places, in their colours and their sense of space and light. They’re not landscapes, but they are about different places.

There’s none of the excitement or action of the earlier works, though. Every painting here sticks to a formula of straight horizontal brush strokes, thickly applied, mostly with an oval carved into the surface of the paint. The paintings here are huge, though, and the scale is perhaps more impressive than the painting.

That scale is a huge contrast to Room 3, Turner’s notoriously tricky Irene Willett Gallery, which is home to a series of smaller, more delicate works using pigment like ground-up rocks on paper. These works carry on the themes of the previous room – bold stripes and ovals – but they’re far more interesting works. They have more soul to them, somehow.

There is also a collection of ephemera, including photos, exhibition invites, and correspondence. They are vital to the exhibition – they give us a glimpse of Clark as a real person.

One letter stands out. In it, Clark tells the curator at California State University that he doesn’t want his work in a show of “Afro-American” artists. Clark was well aware of the problems of racism in the art world, but also refused to have his work pigeonholed in this way. He was a painter, not a Black painter.

And the final gallery shows us his paintings from the 1980s, 1990s, and that final painting from 2005. This room feels the weakest to me. Clark seems to be throwing too many things at each painting – curved bands of different colours, intersected by horizontal lines, and none of the restrained colour choices of his 1970s paintings. There’s no sense of this work being rooted in any time or place. There are little corners of paintings that are great, but the overall impression is of an artist who’s got a bit lost.

Except for that very last work, painted 14 years before he died (that last period is unrepresented here – rather begging the question, what happened?).

Untitled (2005) takes us back to the start. Like the 1960s works, it has a drama and energy to it, with big bold strokes of colour overlaying each other. But like the 1970s works, it’s also rooted a landscape. It feels like, at the end, Clark remembered the excitement of those early years, and his interest in different places, and finally brought the two together. In doing that, he created one of the most successful works in the show.

Ed Clark opens at Turner Contemporary this Saturday 25th May, and runs until 1 September. Admission is free.