During the summer of 1859, late one afternoon as the sinking sun began to kiss the horizon, a little man was returning from an afternoon walk along the Broadstairs coast.

An author by profession, he had gone for wander hoping to come up with a suitable title for his latest story, a psychological thriller full of passion, intrigue and deception. Feeling exhausted, he flopped down on the grass opposite the North Foreland Lighthouse.

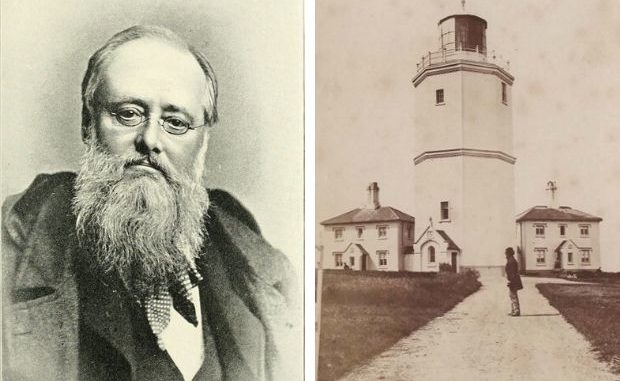

Standing isolated and exposed upon the headland, its beam reaching out to sea, the writer regarded its structure. In the fading light it looked eerie — even spectral. After a moment’s contemplation, he said: ‘You are ugly and stiff and awkward; as stiff and as weird as my white woman’. He paused. ‘White woman,’ he said to himself, ‘Woman in white — the title, by Jove!’

The man was Wilkie Collins and he had just named the first of the two novels which he is today best remembered (the second being The Moonstone).

Born in 1824, both Broadstairs and Ramsgate were regular haunts in his life and would also be influential in his work. His first trip to Thanet had been a family holiday in 1829. Wilkie’s father was the landscape and genre painter William Collins. Part of the Romantic movement of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, William counted amongst his friends the poets, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey and William Wordsworth. Indeed, the trip to Ramsgate was on Coleridge’s recommendation.

Ramsgate during this time was just beginning to develop as a seaside resort. Ever since Princess Victoria’s visits during the 1820s, the town had become a fashionable watering-hole for London’s elite. Much of what is today urbanised was back then still fields. For young Wilkie it was a place of adventure. He learnt to swim in the sea and was generally bewitched by the town and its people.

There were other family holidays to Ramsgate but during the 1850s and 60s Wilkie also fell in love with Broadstairs, favourite haunt of his friend Charles Dickens. Collins would regularly stay there with his mistress Caroline Graves and her young daughter.

In August 1859, they took a six week lease on Church Hill Cottage, which overlooked the sea on the Ramsgate Road. Here he continued to work on The Woman in White, which was later serialised in All The Year Round. But during this visit, Wilkie health began to suffer and would continue to plague him for the rest of his life.

While renting Fort House, where he worked in part on No Name (1862), Collins was again struck by a nervous seizure. His younger brother, Charles, was convinced Wilkie’s profession was having a detrimental effect, saying: ‘Your work is tiring work’. The atmosphere in the house was at times very tense because of it, and Wilkie quarrelled with two of his servants so much that they left (though it’s not known whether they resigned or were dismissed).

When Dickens died in June 1870, the love affair with Broadstairs was over. The town had become ‘the most dreadful place in the world’ and held ‘too many memories’. Remembering happy childhood holidays, Ramsgate became his new refuge.

Out of the two Thanet towns, Ramsgate had the biggest influence on his work. It held scenes in many of his later novels, including Poor Miss Finch (1872) and The Law and the Lady (1875). In his 1879 novel The Fallen Leaves, he paints a vivid picture of Victorian Ramsgate: ‘…the cries of the children at play, the shouts of the donkey boys driving their poor beasts, the distant notes of brass instruments playing a waltz, and the mellow music of small waves breaking on the sand’.

When not staying at the Hotel Granville (where he completed The Haunted Hotel in 1878), Wilkie would either rent 10 Nelson Crescent (above) or 27 Wellington Crescent (below). His person life was somewhat complicated. As well as his mistress, Caroline Graves, he also had a common-law wife called Martha Rudd, with whom he had three children.

In order to avoid scandal, when chaperoned by Caroline he’d stay at Nelson Crescent, but when accompanied by Martha he rented Wellington Crescent, and used an alias – William Dawson. The subterfuge even went as far as Wilkie informing close friends that all correspondence to Wellington Crescent should be addressed accordingly, telling them that, ‘Wilkie Collins… has disappeared from this mortal sphere’.

During the 1870s and 80s, Wilkie’s health continued to deteriorate and in June 1889 he suffered a stroke which left him paralysed on his left side. This would be his last visit to Ramsgate.

Three months later Wilkie Collins was struck by a second stroke. He died in London on September 23 and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.