The situation was dire but when wasn’t it?

Repeatedly they tried to launch into the boiling sea, and with every attempt they were driven back to shore. The crew of the Broadstairs lifeboat, Mary White, knew that time was of the essence, but they also knew that further attempts to launch from Viking Bay would be futile.

But like lifeboat crews before and since, quitting wasn’t an option. Described by one eye witness, John Lang, in a letter to the Times, as being ‘renowned for their alacrity’, the Mary White’s crew dragged her back upon her launch trailer and with all haste headed over the hilly terrain towards North Foreland.

Two miles around the coast, the Northern Belle, a 1,100 ton American cargo ship, had moored off Kingsgate. She had been en-route from New York to London but, during the early hours of Monday 5th January 1857, weather conditions deteriorated so much she had decided to drop anchor and attempt to ride the storm out.

Now straining against her anchor cables, with waves breaking over her deck, it looked inevitable that the tortured ship and her crew would be lost in the heavy swells of a tempestuous sea.

By the time the Mary White had been hauled overland to Kingsgate, the Belle’s crew had already cut away both the mizzen and main masts. ‘The ship then rode easier,’ Lang wrote, ‘but as the day advanced the gale increased in violence, and the sea ran proportionately high.’

With the Mary White was her sister vessel, Culmer White. At 30 ft. long, both had been presented to Broadstairs by Mr Thomas White of Cowes, Isle of White, a few years earlier.

From Margate, two luggers (type of fishing boat), Ocean and Victory, were already attempting to aid the Northern Belle’s imperilled crew. Ocean had already managed to get five hands aboard, with Victory hovering on standby to offer further assistance.

News of the cargo ship’s plight spread like wild-fire throughout Thanet, and, in spite of the atrocious weather, a vast crowd gathered to watch the unfolding drama. ‘…by 11 o’clock,’ Lang observed, ‘the cliffs were crowded by persons of all ranks’.

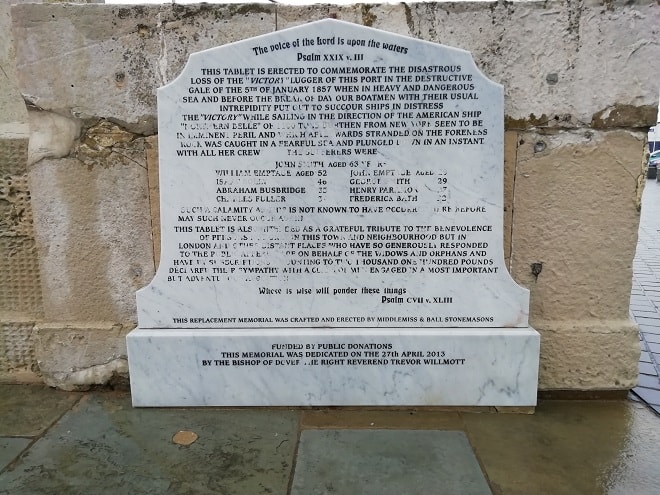

Some thirty minutes later, these spectators watched in horror as the Victory was hit and rolled over, disappearing from sight and taking her crew of nine with her. The Ocean immediately attempted a rescue and nearly suffered the same fate.

All through the day onlookers watched, expecting the Northern Belle to be driven on the rocks, but the ship defiantly clung to her anchorage.

The howling storm, ever growing in its ferocity, now added sleet and hail to its arsenal, severely reducing visibility and making it impossible to launch the lifeboats. Night was falling and the fate of those stranded aboard the doomed vessel must have appeared sealed.

Dawn broke to find the Belle upon the rocks and the men stranded on her tied to the only mast left standing.

With visibility improved, the Mary White launched into the still angry sea. On several occasions she disappeared from sight. The crowd held its breath — hoping — praying the ten brave men had not suffered the same fate as the Victory’s crew. The lifeboat managed to rescue seven men but suffered damage to her bow.

Now unseaworthy, the Culmer White put to sea, returning fourteen souls to the shore, leaving only the Belle’s Captain Tate and a pilot picked up from Dover aboard.

When the Culmer White returned, Tate declared that he would rather perish with his ship than desert her. The pilot also expressed a reluctance to leave. After a heated exchange of words between the captain and the lifeboat crew, the Culmer White returned to shore, leaving the now abandoned Northern Belle to the wrath of the sea.

There were cheers from the crowd as the Americans, the lifeboat crews and the five men from the Ocean were taken to the Captain Digby Inn. The celebrations continued as the two lifeboats were hauled back to Broadstairs, as recalled by Lang:

Tied to an oar was the American standard, which was so recently hoisted as a signal of distress. The tattered flag fluttered over the broken bow of the Mary White. It was thus that the boats passed through the streets of Broadstairs amidst the joyous shouts of the inhabitants…’

A collection was raised for all those who participated in the rescue and each received a silver medal from the American Embassy on the instructions of President Franklin. For the widows and orphans of the Victory £2,100 was raised and a marble tablet erected on Margate jetty in memory of the valiant lugger and her courageous crew.