William Ward was feeling very agitated. The hour was getting late and his wife, Thomasina, had failed to return home from visiting their daughter.

Earlier that cold mid-January evening in 1807, he had gone out looking for her, expecting to meet the 63-year-old along the way, but when he arrived at his daughter’s house in Broadstairs (sadly her name isn’t recorded), he was told that Thomasina had left two hours earlier.

William immediately returned home to St Peter’s, where they both ran a Chandlers shop, again hoping to meet his wife but again there was no sign of her. He raised the alarm forthwith.

Friends and neighbours began a search and as St Peter’s Church clock struck midnight, her battered body was discovered in a field, sixty yards from St Peter’s Road (in the vicinity where Hilderstone College now stands).

Thomasina’s body lay on its back. Her clothing was in a “very disordered state” and her pockets had been removed. There was also evidence that she had been raped before being strangled with a piece of ribbon. Her mouth was open and a wet handkerchief lay next to her corpse suggesting she had been gagged.

Robert Barfield was the Sub-Deputy for St Peter’s and, assisted by the Parish Constables, he now investigated what the Kentish Gazette described as “a murder…of brutal depravity”.

One witness to come forward was Henry Blackburn. A carpenter by trade, he had seen Thomasina just minutes before she was murdered as he headed towards Broadstairs. They had paused to chat. She was in good health, Blackburn later testified at the Maidstone Assizes.

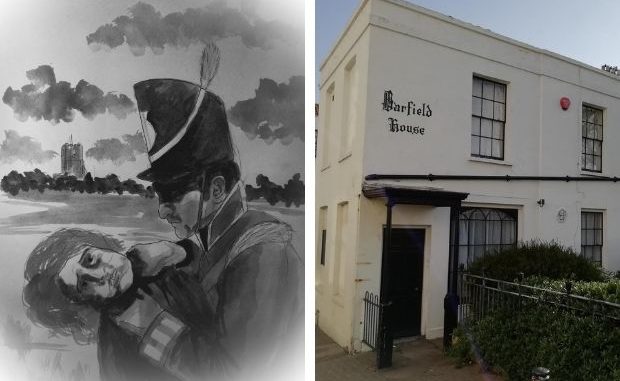

Blackburn would be the investigations key witness, for minutes earlier he had passed a soldier dressed in the uniform of the King’s German Legion.

The KGL was a British Army unit of mostly German expats fighting against the French in the Napoleonic Wars. The 7th Battalion was based at Ramsgate but they also had a garrison in Broadstairs and it was here that Barfield headed.

There he enquired whether anyone had been absent during the time of the murder. Sergeant Frederick Riford was the officer he spoke to but also present was a Private Andrew Schestack (referred to in some press reports and official records as “Andreas Shostack”).

The two men noticed that Schestack (28) appeared “much alarmed and confused” as Blackburn explained the reason for his visit. It transpired that the young private had gone AWOL on the night of the murder. A search of the barracks revealed personal effects belonging to the victim.

Schestack was arrested and later claimed he had been drinking in the Neptune pub from 7pm to 10pm. that night. But later inquiries revealed he had left at around 8.30pm.

Initially, the private confessed, saying that, previous to meeting Thomasina, he had been “accosted” by a man dressed in a sailor’s uniform. Together they had beaten and robbed the helpless woman.

A sailor fitting Schestack’s description was arrested in Ramsgate and they both appeared before the Coroner, Thomas Mantel, who was assisted by London barrister, William Garrow. But while the evidence against Schestack was pretty damning, that against the sailor called Webb was deemed insufficient and he was released.

Andrew Schestack, however, was remanded to Dover Gaol to await trial at the next Maidstone Assizes, where he was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Unable to speak a word of English, the court’s proceedings were relayed to him via an interpreter. Schestack tried to save his neck by claiming he wasn’t responsible for Thomasina’s murder. Webb, he claimed, had given him Mrs Ward’s handkerchiefs after he’d attacked her.

After sentencing, the German is reported to have said: “there is one God, and one heaven” and that he would pray for mercy. Judge Heath told the prisoner not to expect it in this world.

Two days later, on Saturday 28 March, Andrew Schestack was conveyed from Maidstone Gaol to Pennington Heath and there executed.

The Kentish Gazette reported how the young German now appeared “broken and enfeebled” and was attended by a Catholic Priest. After he was turned off, the Gazette concluded, he gave one convulsive struggle, and immediately expired. Despite fully understanding the gravity of his situation, Andrew Schestack protested his innocence until the end.