Just after 9 am three gunshots rang out from 38 King Street, Ramsgate, home of a William Ellis.

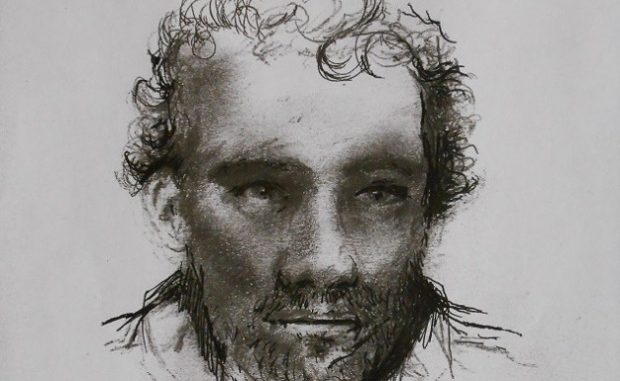

Ellis, 68, a dyer and scourer by profession, lived at the address with his daughter Adelaide, 34. Also with them that Thursday morning, 10 August 1865, was their friend and neighbour Mary Forwood, 36, and her eight-year-old daughter, Emily. All were expecting the arrival of Mary’s estranged husband, who had made a sudden reappearance the previous evening.

Life had been tough for Mary since Stephen, 36, a former baker from the town, had abandoned her eight years earlier. Their eldest child, Herbert, had died aged 7 of tuberculosis and through a combination of hard graft working as a dressmaker, Parish Relief and the generosity of the Ellis’ she had just managed to keep Emily and herself out of the local workhouse. But now Stephen had returned and things looked set to improve.

Upon his arrival, Stephen declined the offer of breakfast. Adelaide suggested that the couple use the upstairs living-room to discuss anything private. A few minutes later Mary asked that Emily also join them.

Miss Ellis had just set about attending her morning chores when two pistol shots rang out. By the time she had reached the foot of the stairs, Emily’s body had rolled down onto the landing. Adelaide looked on in terror as Stephen Forwood slowly descended the stairs, a revolver in hand. ‘Forwood, what are you doing!?’ she screamed.

A third shot rang out.

From his workshop, William Ellis had heard the shots but took no notice. The reports of firearms in Ramsgate at this time weren’t unusual, with retail outlets selling them openly over the counter. It’s only his daughter’s desperate pleas as she hurried into the back-yard that finally alerted him something was terribly wrong.

Press reports of the time portray the sexagenarian bounding up the stairs and leaping over little Emily’s body and rushing into his living-room. Whatever the reality, he finds Forwood with his back to the door, pistol in his left hand, smoke still issuing from the barrel.

‘What have you done?’ William asks incredulously.

Forwood made no reply. The dyer demanded the weapon be handed to him. Forwood complied immediately, saying that his murderous deeds were an act of charity and that he was already under a death sentence. What the Ellis’ didn’t know at the time was that Forwood, under his pseudonym of Ernest Southey, had already murdered his lover’s three sons in London two nights before and was now sought by Scotland Yard.

Distraught at the sight of Mary’s body, William commented how Forwood had ‘brought ruin upon my house’. The murderer coolly replied that Ellis would be compensated for any financial losses.

After his arrest, Forwood repeatedly attempted to lay the blame for his crimes upon society, especially those in authority, such as Scotland Yard Commissioner, Sir Richard Mayne, and Prime Minster Lord Palmerston, who had ignored his murderous warnings. He also claimed to have won £1,170 in a billiard contest in Brighton but had been cheated out of his winnings.

Before Ramsgate Magistrates, and later at the Maidstone Assizes, Forwood repeatedly disrupted proceedings, either by prevaricating to direct questions or succumbing to fits of wild anger. His defence tried to establish that he was suffering from monomania but the jury weren’t convinced, especially when it transpired that after descending the stairs, he placed the revolver’s barrel in Emily’s mouth and pulled the trigger. They took less than ten minutes to pass a guilty verdict.

Stephen Forwood was hanged outside Maidstone Gaol on 11 January 1866 and buried within the prison’s complex. He remains there to this day.