Altruism, selfless concern for others, is meant to be the opposite characteristic of egoism, selfish concern for oneself.

But then, publicly wanging on about one’s altruism seems quite like egoism, in truth. I can understand people doing great charitable deeds and endlessly talking about it. Their peers assume they are good eggs. Their egos are stroked. They are probably trying to compensate for their own sense of inadequacy. Most of us do it, one way or another.

When they neglect their families and loved ones in order to perform their flamboyant charitable works – for you don’t get nearly so many ‘likes’ on Facebook for publicly caring for your partner, parents, children, particularly if you’re female – it can tip into a narcissism that borders on the pathological. Telescopic philanthropy, Dickens called it: only caring for distant strangers, ignoring the friends and family with an arguably greater, but less glamorous, claim on your time and energy.

It’s wearying, but understandable. I’ll do anything for attention myself.

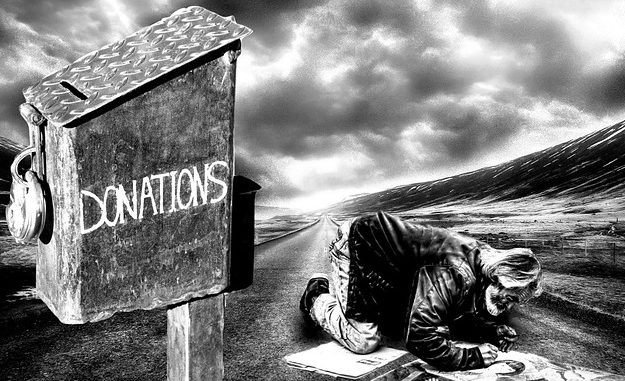

From an evolutionary perspective, true altruism – secretly giving to strangers, expecting no return – makes absolutely no sense. Of course, you still get the glow of thinking yourself a good fellow, even if no one else knows it; you might even believe that God will be pleased with you and give you a cushy seat in Heaven.

Or you might be motivated by something darker.

I’ve watched the Oxfam scandal unfold with a resigned, world weary despair, even as it spread to other charities, Save the Children, Plan International, and twenty odd others.

It’s often the case that those making headlines do so for unpleasant reasons. And of course there are some who genuinely feel an urge to alleviate suffering, who struggle to sit easy in a world where people are cold, hungry, destitute. Certainly, I abhor the strain of right-wing argument which suggests foreign aid should come to an end, and then latches on to this scandal as a means of bringing that about. For many practical and philosophical reasons, foreign aid is utterly essential.

Nonetheless, the urge to help emerges from the same place as the urge to exploit. It’s a desire to make yourself feel better at the expense of the vulnerable. Rather than seeking out relationships with equals, there are those inadequate aid workers that flock eagerly, vulture-like, to the poorest, most desperate parts of the globe to patronise the suffering and needy, to enjoy the warm glow of feeling worthwhile and necessary. They seek power, rather than an end to misery. And power, dominance, mastery over the vulnerable, can so easily tip into the erotic. I’ve never read or seen Fifty Shades, thank goodness, but all the same, I understand the connection.

If the world were equal and happy and all suffering were at an end, these people would be horrified. How would they spend their days then? Where find the thrill that gives life its zest?

It’s the same urge that sees women fall in love with men on Death Row. Our culture encourages us to see romance through the paradigm of rescue, heroes, knights on horseback – see Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Pretty Woman. We learn from infancy that rescue by hero is romantic. While victims are symbolic and the rescue is in progress, the vulnerable remain intriguing: when they are actually flesh and blood, smelly, annoying human beings, we lose interest, and when they don’t act properly grateful, or stay rescued, they incense us, and we treat them brutally.

It’s often said that those wishing to become politicians should automatically be barred from seeking office: those keenest to lead and enjoy power over their countrymen should on no account be allowed anywhere near the political system. The same, I would argue, should be said of aid workers.

Do-gooders eager to distribute aid should be let nowhere near the needy. While the world stays so stinkingly unfair, and aid remains a sad necessity in war torn lands, refugee camps, disaster zones, its distribution should be performed by first world citizens chosen randomly, like jurors.

Do them good, I expect. Open their eyes to how amazing their lives are: stop them moaning about slow broadband and roadworks. But those who actually want to devote their lives to assisting the destitute should on no account be let anywhere near them. The urge is exploitative and must be resisted. Lock your passport away and get some therapy.