A tale from Ramsgate features in a book of 56 Victorian cases of murder that were covered in the sensational weekly penny journal the Illustrated Police News between 1867 and 1900.

The Illustrated Police News was an early form of tabloid paper, using graphic sketches to illustrate its stories.

It and others like it were referred to as Penny Dreadfuls, as they cost just one penny for a weekly digest of eight, murder packed pages.

The compilation of pictures forms part of the book Victorian Murders, by crime writer and Cardiff University professor Jan Bondeson on December 15.

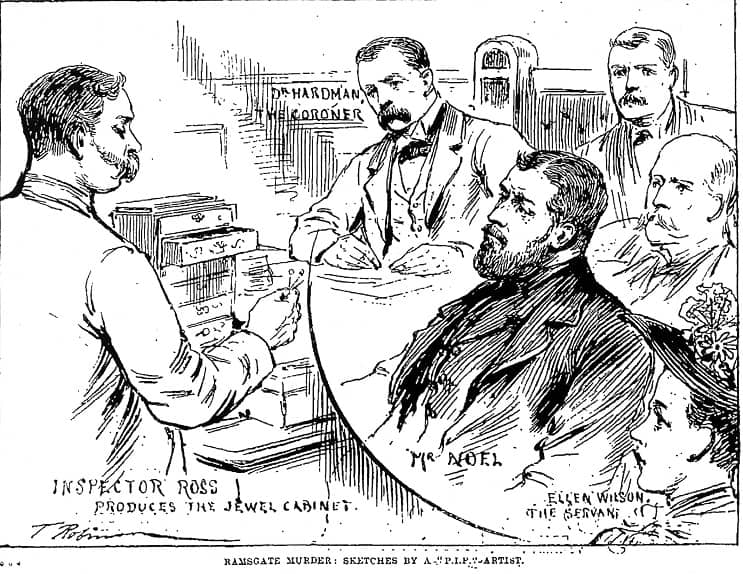

One of the takes featured is the ‘Ramsgate Mystery’ of 1893, in which the local butcher William Noel stood accused of murdering his wife at 9 Adelphi Terrace [today 20 Grange Road, the murder house stands]. The case was thrown out of court due to insufficient evidence, and the murder was never solved.

Victorian Murders was published by Amberley Publishing on December 15 is available here: https://www.amberley-books.com/victorian-murders.html

The Ramsgate Mystery

by Jan Bondeson

William Noel was born in 1860 and became a journeyman butcher in Whitechapel, before moving on to Southsea. Here he met Miss Sarah Dinah Saunders, a woman of independent means who ran a lodging-house. Although Sarah Dinah was ten years older than the sturdy, bearded young butcher, they began ‘walking out’, and married in 1878.

After some debate whether to stay in Southsea, or perhaps move to London, Noel made use of his wife’s money to purchase a butcher’s shop at No. 9 Adelphi Terrace, Grange Road, Ramsgate. The butcher’s shop had a large display window to the front, and a smaller window to an alley on the side. Behind the shop was a small sitting room, with a door to the side, and another door to the kitchen and scullery. A small yard separated the house from the stables and workshops where Noel and his assistants butchered various animals, and prepared their meat for sale.

Initially, William Noel’s butcher’s shop met with difficulties, and he had to borrow £150 from his wife’s father to keep it running. A steady, industrious man, Noel worked hard to make his business a success, travelling into the countryside to buy livestock, and employing two journeymen and a lad. The borrowed £150 was soon repaid, and Noel was able to save some money.

The two Noels were very respectable people, and pillars of Ramsgate lower-middle-class society. They were strict Wesleyans, and active members of their church community. There was of course gossip about this out-of-town childless couple, with the husband being ten years younger than the wife, but although mischievous people were whispering that William Noel was fond of chasing the country lasses when he was out buying livestock, the two Noels appeared to be getting along perfectly well.

On the afternoon of Sunday May 14 1893, everything seemed perfectly normal in the Noel household. After having had his luncheon, William Noel sat in the downstairs parlour and read through the lessons, since he was a society steward at the St Lawrence Wesleyan Sunday School. The Noels had a servant girl named Nelly Wilson, but she was given Sunday afternoon off. Sarah Dinah Noel counted the morning’s collection from church, which amounted to ten shillings, and went to lock the money away.

At around 2.15 pm, William Noel went off to the Sunday school, leaving his wife behind in the company of the family dog Nip, a large and sturdy black retriever. Nip was something of a disreputable dog, who had savaged a number of smaller dogs, and bit one or two children as well. His guarding instinct was in good working order, and when a man had tried a retrieve a chair he had deposited in the Noels’ back yard, the angry and powerful Nip had kept him out.

At 2.20 pm, the neighbour Lavinia Squires saw William Noel walking past her house on his way to the Sunday school. He arrived there at 2.25pm and took part in the teaching until 3.45pm, being observed by many people, and behaving just like he usually did. When leaving the Sunday school, he was accompanied home by some of his pupils, enjoying a theological debate with these juvenile Wesleyans.

When he knocked at the door at No. 9 Adelphi Terrace, there was no response, although he could hear the dog barking. Noel went to see some of his neighbours, and with some difficulty, he entered the back yard and forced open the parlour window. Sarah Dinah Noel was lying on the floor in a pool of blood, quite dead and with a bullet wound to the head. The dog Nip was keeping vigil next to the corpse.

The murder house had been ransacked for money, and the cash-box had been broken into and its contents stolen. The murdered woman was wearing five rings and a watch and chain, but these had not been touched. Chief Constable Bush and Inspector Ross were soon at the scene, to take charge of the murder investigation. They found it curious that although the dog Nip was considered to be of a ferocious disposition, none of the immediate neighbours had heard any barking from the house.

Mrs Noel had been shot at close range, the bullet passing through the head and killing her instantly. When a party of five police constables was detailed to search the murder house, Inspector Ross gave them two bottles of beer from Noel’s cellar for them to be in good cheer. At the coroner’s inquest on Sarah Dinah Noel, the dog Nip was exhibited in court: he showed no appearance of ferocity, but wagged his tail amiably and made friends with some of the bystanders.

Nelly Wilson, the servant girl employed by the Noels, had never heard her master and mistress utter an angry word at each other. The day of the murder, they had both appeared exactly as usual. The dog Nip was in fact quite timid, she said, and sometimes retreated into the corner of the room on hearing an unusual noise. She had to admit, however, that the dog had once flown at her and bitten her hard.

William Noel himself was grilled at length by the coroner and the jury: his wife had been alive and well when he left for the Sunday school; he had never possessed any firearm and did not understand their use; his wife’s life had not been insured. An important witness was Mrs Sarah Dyer, the wife of a chemist who lived not far from Noel’s shop: at 2.45 pm the afternoon of the murder, she had heard Noel’s dog bark and growl, and then a loud report. The dog ceased barking once the shot had been fired, but recommenced at around 4pm, when Noel was returning home.

Inspector Ross decided to try a few experiments to investigate whether the dog Nip was gun-shy. The results were wildly divergent: when a blank revolver shot was fired, the dog merely wagged his tail, but when an alka-seltzer bottle was opened with a pop, the timid canine yelped with fear and ran out into the yard.

At the coroner’s inquest, Dr Fox testified that the assailant had probably stood just four feet away when he shot Mrs Noel; the bullet was a large one, probably emanating from a revolver or pistol of large calibre. Rigor mortis had begun to set in when the body was at the mortuary at 7.30pm, indicating that she had been murdered five or six hours earlier.

A number of witnesses swore to the impressive alibi of William Noel between 2.20pm and 4.00 pm: he had been seen by many people walking to the Sunday school, looking quite jolly and contented, and later returning home accompanied by some of his pupils. Miss Martha Saunders, the spinster sister of Mrs Noel, produced a letter, written in the last month, in which the deceased had referred to her husband: “William, I think, if possible, is more fond of me than ever.”

Two days before the murder, when the two sisters had been at Hastings, Mrs Noel had expressed herself in a similar strain. There was much newspaper interest in the ‘Ramsgate Mystery’, which held its own among the celebrated murders of the day, even in the large London newspapers. A worried local, who despaired of the Ramsgate police’s ability to solve the crime, appealed to Dr Conan Doyle to come to Ramsgate and make use of his Holmesian powers of deduction, but all he received was a polite reply that Conan Doyle was too busy with his professional duties to have time for any seaside crime-solving excursions.

But Inspector Ross did not agree of this benign picture of William Noel. Since a number of valuables had been left at the murder house, he felt convinced that the robbery had been ‘staged’ by the murderer. Since Mrs Noel did not seem to have any enemies, and since the dog had not barked much at the time of the murder, he thought William Noel the prime suspect: he had shot his wife just before leaving for the Sunday school, and then successfully played the innocent husband.

Inspector Ross lent a willing ear to the Ramsgate gossips who spoke of Noel’s immoral activities. The lustful butcher had once employed a young lady book-keeper named Miss Miller, and an old woman had once seen these two in a compromising position, lying together on the floor. A farm labourer had once met Noel, who was coming to purchase some lambs; he had been accompanied by a young woman, for whom he gathered a bunch of wild flowers. Several other rustic witnesses had also seen Noel chasing the lasses when out in the countryside purchasing livestock.

The coroner’s inquest returned a verdict of murder against some person or persons unknown, but nevertheless, Inspector Ross decided to act decisively. At the end of the inquest, he arrested Noel and brought him before the Ramsgate Magistrates, charged with murdering his wife.

In long and gruelling examinations, the magistrates put William Noel under considerable pressure. He vehemently denied having murdered his wife, and called the Almighty as a witness as to his innocence. The Ramsgate Wesleyans showed praiseworthy loyalty to Noel, pointing out that he was a very respectable tradesman, who had promised to subscribe £50 for a new chapel at St Lawrence. Noel was allowed to have his meals sent to him in his cell, brought by his niece Alice Simmons; the dog Nip sometimes accompanied her, but this extraordinary dog is said to have shown the utmost indifference to the plight of its master.

A number of witnesses told all about the immoral butcher’s many young lady friends, and a treacherous Wesleyan testified that Noel had once been accused of indecently interfering with one of his Sunday school pupils, although he had indignantly denied this offence at the time. When cross-examined, Inspector Ross declared himself convinced “that the alleged robbery was a bogus one, and Noel the author thereof.”

Defending William Noel, Mr Hills deplored that “The whole country had been scoured to find something against the prisoner’s moral character, and it was a monstrous thing that a man should be branded in this way for incidents in his career which had nothing to do with the alleged offence under notice.”

There was no motive for Noel to murder his wife, and the police would have been well advised to track down the intruder, and find the murder weapon, instead of listening to malicious gossip about his client. But the outcome of the magisterial inquiry was that Noel was committed to stand trial for murder at the Maidstone Assizes.

When charging the Grand Jury at Maidstone, Mr Justice Grantham paid particular attention to the Noel case. He boldly declared that the evidence against William Noel was wholly inadequate. Indeed, “In the whole course of his experience he had never met with a case in which there was, on the part of the prosecution, so much incompetence, impropriety, and illegality.

During the sixteen days the case was before the Magistrates there was not adduced more evidence than might be compressed into one small piece of paper.” The police had been guilty of vastly exaggerating the case against Noel, and the gullible magistrates had willingly played along. Of course, it remained possible that Noel had committed the crime, but his own task was to evaluate the quality of the evidence against him, and the facts of the case did not at all support the guilt of the Ramsgate butcher.

After such an angry juridical tirade from Mr Justice Grantham, the only action open for the Grand Jury was to throw out the bill against William Noel; the butcher was set at liberty, and reunited with his niece Alice Simmons and the dog Nip.

There was dismay in Ramsgate when Mr Justice Grantham and the Grand Jury threw out the bill against William Noel, and the butcher was set free. Over £50 was subscribed to a testimonial to Inspector Ross, who had been so severely criticized by the judge. Local opinion was very much against William Noel, and he never returned to Ramsgate: the butcher’s shop was sold, and Noel’s name erased from the shop front.

Did Noel change his name to William Jolly, and did he open another butcher’s shop in a different part of the country, and marry another wife; on a quiet Sunday afternoon, did he sit contentedly in his parlour, having a swig from his tankard of beer, and giving the dog Nip a nice meaty bone?

Or did he become William Furtive, a Ramsgate Ahasverus wandering from town to town pursued by his notoriety, accompanied only by the Black Dog of Guilt; and was he fearful that his sinister companion, the sole witness to the murder of Sarah Dinah Noel, would one day become a formidable Dog of Montargis, bent on vengeance for the dead, and devour him?

The evidence against William Noel for murdering his wife largely rests on the persistent local gossip that he was a philanderer who indulged in immoral conduct with various floozies, behind the back of his wife. It may be speculated that he was tired of his much older spouse, and wanted to get rid of her to be able to remarry and have children. Experienced policemen suspected that the burglary was staged, and the dog Nip would not appear to have barked at the murderer, perhaps because it was his own master. And would a burglar have shot the woman dead and allowed the large and powerful dog to live?

In defence of William Noel, it must be pointed out that he had a rock-solid alibi from 2.20pm, when he was seen walking to the Sunday school, until 3.55 pm, when he was seen returning to No. 9 Adelphi Terrace. If the woman Sarah Dyer, who claimed to have heard the dog growling and barking at 2.45pm, and then the report of a shot, was telling the truth, then Noel must be innocent.

Noel did not have a criminal record, he had no access to firearms, and he was not taken in any lie or contradiction by the police. And what kind of hypocrite would murder his wife in cold blood, before going to the Sunday school to disseminate his unctuous sentiments to the wide-eyed scholars?

The evidence against William Noel was clearly not sufficient for him to have been found guilty in a court of law, and Mr Justice Grantham did the right thing when he threw out the bill against him. The forthright Judge was also right to criticise the Ramsgate police, who made their minds up that Noel was guilty from an early stage, and failed to investigate alternative suspects; quite inexperienced when it came to investigating mysterious murders, they would have been well advised to apply for an experienced Scotland Yard detective for assistance.

According to Ramsgate directories from the 1880s, Adelphi Terrace had originally been a terrace of eight Victorian houses in Grange Road, between St Mildred’s Road and Edith Road, with shops on the ground floor and two upper stories. Separated from the others by a small alleyway, No. 9 and No. 10 were later additions. The houses were later incorporated into the numbering system for Grange Road, No. 9 Adelphi Terrace becoming No. 20 Grange Road.

The former butcher’s shop is today the ‘China City’ takeaway, but the building looks virtually unchanged since 1893, except that the side door has been moved to the rear extension. At the bottom of the yard behind the house, William Noel’s stables still remain, albeit in a dilapidated condition.